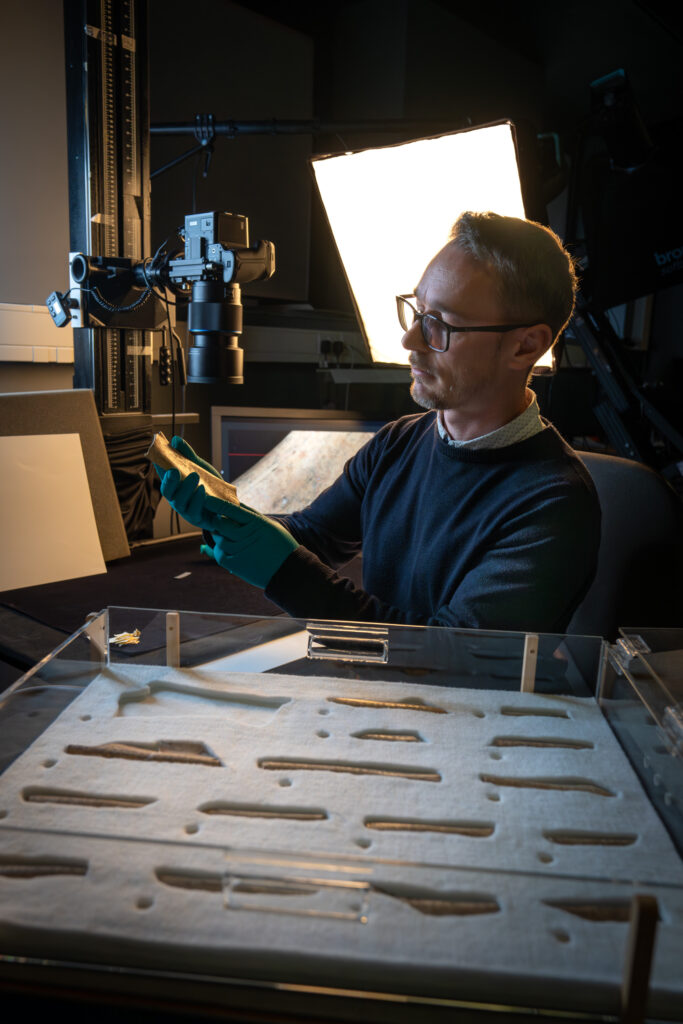

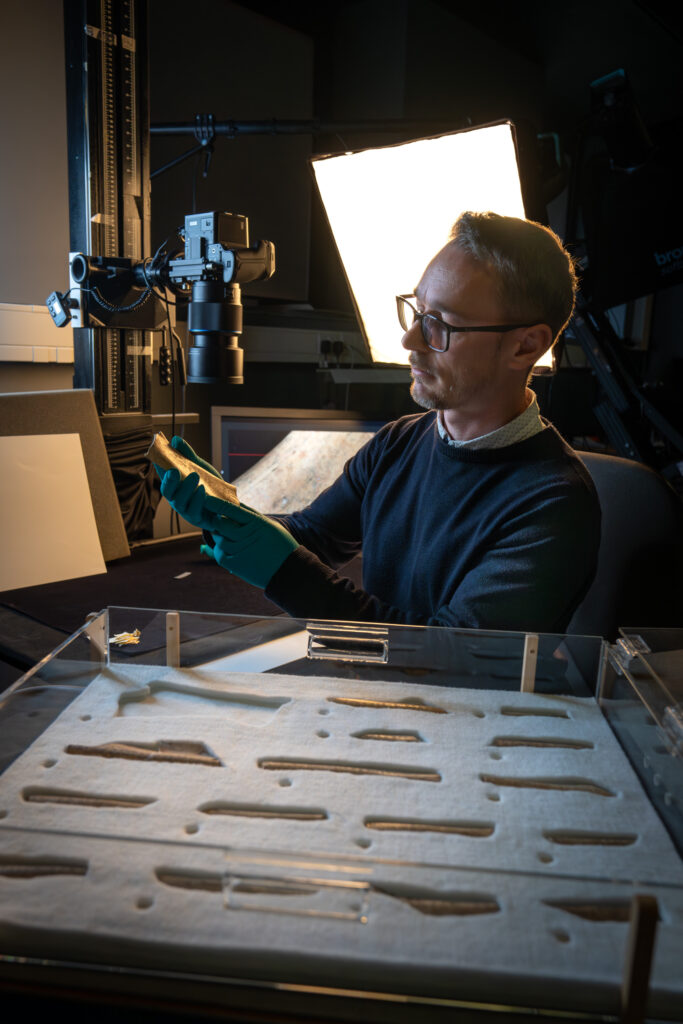

Błażej Mikuła is a team member of the Cultural Heritage Imaging Laboratory (CHIL) at Cambridge University Library. He is involved in digitising manuscripts and creating short films for various projects.

Previously, Błażej worked as a photojournalist, capturing significant historical events such as the war in Afghanistan and the famine in South Sudan. Now, he is rediscovering the hidden past in books using modern technology like multispectral photography. He has contributed to several projects, including , Newton, Darwin, Genizah Project, and more. Currently, he is working on the Wong Avery project, where he creates 3D scans of Chinese oracle bones, allowing for the digital reconstruction of previously broken bones.

Spending long hours in the library had an unexpected side effect—he caught an interest in book collecting. Today, he owns a vast collection of “Klubówka” — pirated editions of science fiction and fantasy books printed in Poland during the collapse of communism, between 1980 and 1990. These were the first Polish editions of iconic works such as Conan, Star Wars, and I, Robot by Isaac Asimov. Often poorly translated, crudely printed, and unquestionably illicit, these books are relics of a time when literature slipped through the cracks of censorship — smuggled in ink and paper.

1. How do you define Digital Humanities?

This is where curiosity meets computation—using technology to deepen our understanding of culture, history, language, and society. Whether it’s exploring why 11th-century scribes in the Middle East chose specific inks or recovering erased text from an ancient palimpsest, Digital Humanities (DH) offers innovative ways to uncover answers. It brings together scholars, coders, librarians, photographers, and others to collaborate across disciplines. Tools like multispectral photography, reflectance transformation imaging, and 3D scanning reveal insights that would otherwise remain hidden. By bridging the past and the present through digital tools, DH not only transforms how we study the humanities—it redefines what’s possible when we ask new questions in new ways.

2. How did you become interested in DH?

It wasn’t love at first sight—mainly because I simply didn’t know what it was. At first, I was just a photographer, and my task was to make images. I joined the Parker on the Web project at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, in the same year Apple introduced the first iPhone, Netflix launched its streaming service, Amy Winehouse’s Rehab played on the radio, and the Doomsday Clock moved from 7 to 5 minutes to midnight.

It took some time before I realized I could be more involved in Digital Humanities. When new technology came along, I jumped right on it. Today, I’m working with MSI, RTI, and 3D scanning, helping researchers uncover the mysteries of some of the most beautiful items in the library.

I consider myself lucky to have witnessed the growth of DH—from a time when barely anyone applied for the job. It was an amazing time—though today, we’re just 89 seconds to midnight.

3. Tell us about one of your DH projects

It’s dragons and magic. In 1899, when Wang Yirong—a Chinese scholar and official—visited a medicine shop, he noticed inscriptions on what were being sold as “dragon bones.” This marked the beginning of oraculology and the study of the earliest known form of Chinese writing.

Today, the Wong Avery Project—a collaboration between the University of Cambridge and UC San Diego—is cataloguing and digitising the Chinese Collection. We’ve already photographed all of the oracle bones and created several 3D scans with cross-polarised textures. There’s still plenty to do, and—as is typical in Digital Humanities—I’m waiting for someone to ask a new question—preferably one that would allow me to create a CT scan of CUL.52

4. And a DH project you like?

Small Performances is an interdisciplinary project exploring the history and future of printing through the unique collection of typographic punches made by John Baskerville (1707–1775), now housed at Cambridge University Library. Supported by the CHERISH Hub, it brings together historians, scientists, and craftspeople to reconstruct 18th-century punch-cutting using a combination of pioneering scientific and artisanal methods. These efforts benefit both modern industry and education. While my role is limited due to commitments with the Wong Avery Project, I’m contributing 3D models and a short film documenting stone letter carving.

介绍Błażej Mikuła

Błażej Mikuła是剑桥大学(Cambridge University)图书馆文化遗产影像实验(Cultural Heritage Imaging Laboratory)的团队成员。他参与手稿的数字化工作,并为多个项目制作短片。

此前,Błażej 曾是一名新闻摄影记者,记录了包括阿富汗战争和南苏丹饥荒在内的重要历史事件。如今,他借助多光谱摄影等现代技术,在书籍中重新发掘被遗忘的历史。

他曾参与多个项目,包括牛顿 (Newton)、达尔文(Darwin)和开封吉尼扎(Genizah Project)等。目前,他正参与“黄艾芙丽项目”(Wong Avery project),通过三维扫描技术对中国甲骨文进行数字重建,使原本破损的骨片得以“复原”。

长时间待在图书馆意外激发了他对藏书的兴趣。如今,他拥有大量被称为“Klubówka”的书籍收藏——这些是波兰在20世纪80至90年代共产主义崩溃期间印制的科幻与奇幻类盗版书籍。这些书包括《科南》,《星球大战》,以及艾萨克·阿西莫夫的《我,机器人》等著名作品的波兰首译版。这些书往往翻译粗糙、印刷简陋,显然属于非法出版物,却是那个时代的历史遗物——当文学通过油墨与纸张,在审查制度的缝隙中流通传播。

1. 您如何定义数字人文?

数字人文是好奇心与计算技术的相遇——运用科技加深我们对文化、历史、语言与社会的理解。无论是探究11世纪中东文士为何选择特定墨水,还是从古老的重写羊皮纸中恢复被抹去的文字,数字人文(DH)都为我们提供了创新的方法去寻找答案。它汇集了学者、程序员、图书馆员、摄影师等各类专业人士,共同开展跨学科合作。多光谱摄影、反射变换成像(RTI)、三维扫描等工具揭示了原本隐藏的细节。通过数字工具连接过去与现在,数字人文不仅改变了我们研究人文学科的方式,更重新定义了当我们用新方式提出新问题时,研究能达到的可能性。

2. 您是如何对数字人文产生兴趣的?

这并不是一见钟情——主要是因为我一开始根本不知道它是什么。起初,我只是一个摄影师,我的任务就是拍照片。我是在苹果发布第一代 iPhone、Netflix 启动流媒体服务、艾米·怀恩豪斯的《Rehab》在广播中播放、末日时钟从午夜前7分钟拨到5分钟的那一年,加入了剑桥科珀斯克里斯蒂学院的“帕克网页项目”(Parker on the Web)。

过了一段时间,我才意识到自己可以更深入地参与数字人文。当新技术出现时,我毫不犹豫地投入其中。如今,我使用多光谱成像(MSI)、反射变换成像(RTI)和三维扫描,帮助研究人员揭示图书馆中最精美藏品背后的奥秘。

我觉得自己很幸运,见证了数字人文的成长——从几乎没人申请相关职位的时期走到今天。那是令人振奋的时光——尽管现在,我们距离“午夜”只剩下89秒。

3. 请告诉我们一个您的数字人文项目?

这个项目与龙和魔法有关。1899年,中国学者兼官员王懿荣在药铺中发现被称为“龙骨”的药材上刻有文字。这一发现开启了甲骨学的研究,并引发了对中国已知最早文字形式的深入探讨。

如今,“黄艾芙丽项目”(Wong Avery Project)是剑桥大学与加州大学圣地亚哥分校合作开展的项目,致力于整理和数字化中国馆藏。我们已经完成了全部甲骨的拍摄,并制作了多个带有交叉偏振纹理的三维扫描模型。目前还有大量工作待完成,而正如数字人文领域的一贯特点——我正在等待有人提出一个新的研究问题,最好是那种能让我为 CUL.52 进行CT扫描的问题!

4. 您特别喜欢的一个数字人文项目?

“微型演出”(Small Performances)是一个跨学科项目,通过剑桥大学图书馆收藏的约翰·巴斯克维尔(John Baskerville, 1707–1775)字体冲头,探索印刷术的历史与未来。在 CHERISH Hub 的支持下,该项目联合历史学家、科学家与工艺师,利用先进的科学与传统手工相结合的方法,重建18世纪字体雕刻工艺。这些努力不仅对现代工业有益,也推动了教育发展。

尽管我因参与黄艾芙丽项目而无法全程投入该项目,但我仍参与了三维建模,并制作了一部关于石刻字母雕刻过程的短片。